Haz clic aquí para leer la versión español.

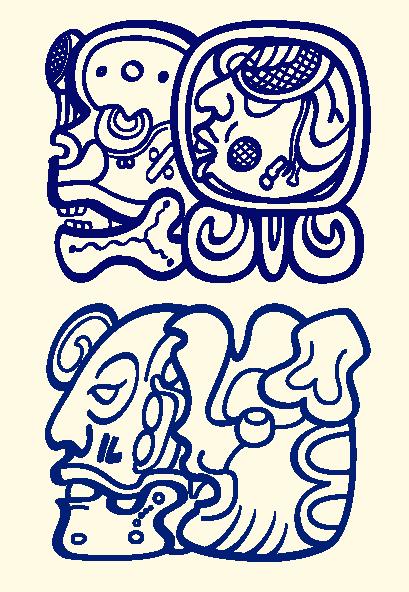

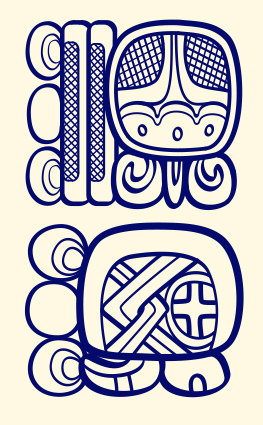

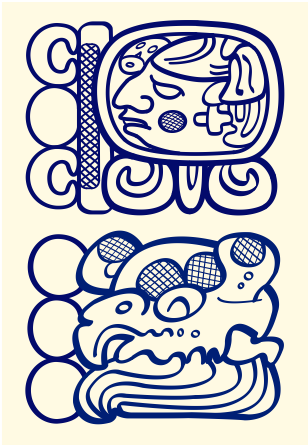

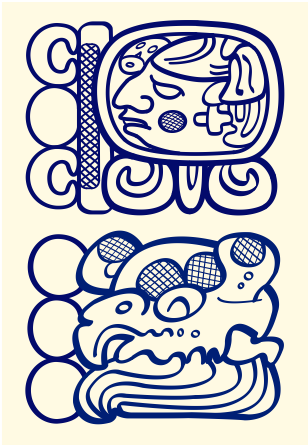

6 Ajaw 3 Muwan: Dibujo de Jorge Pérez de Lara

Of Cabbages and Kings: “Banana Republics” and the Past and Present Fragility of Democracy

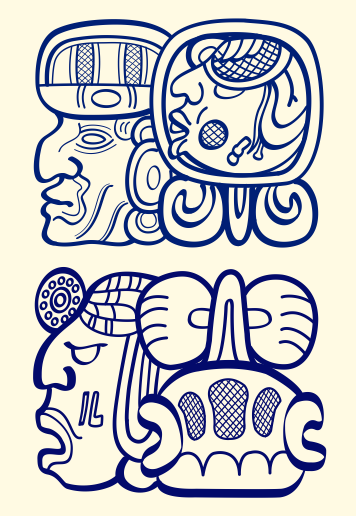

La Gloriosa Victoria, Diego Rivera (1954) Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts.

Gobierno de Álvaro Colom, Guatemala 2008-2012 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

With a heavy heart, I write this to you in a time of grave national crisis in the United States, as yet unresolved, amidst the prolonged catastrophe of a global pandemic through which we all continue to suffer. A New Year is upon us in the Gregorian Calendar, with the promise of a vaccine, which some of my friends have already received but which is not yet widely available. In what will be a fraught two weeks of uncertainty, a new presidential administration comes to power in the United States. Though we lack any current reports to publish from the field, I had hoped to be able to simply wish all of us a happier and more hopeful year ahead, which I certainly wish for all of us, now more than ever. But I am feeling that now is not the time to remain silent regarding what is happening. Please forgive my departure from our usual topics in my turning to current events, but there is a thread that I feel needs to be explored that connects us to a lesser-known, shared history between the United States and Maya people which is often not discussed or acknowledged.

The attempted coup d’etat and the tragically deadly forced invasion of the U.S. Capitol Building on January 6th has been a shocking new experience for citizens of the United States, which prides itself as being the global beacon of democracy. This insurrection continues to be a painful, yet important reminder of the fragility of democracy itself, and it is important for us to recognize that this kind of event and its tragic aftermath is not unfamiliar to much of the rest of the world, particularly for our many Maya friends in Central America who are watching this from the outside and no doubt comparing it with their own painful histories of coups d’etats that have been much more deadly and organized than this one.

With great concern and without hesitation, world leaders and former U.S. Presidents alike have justifiably condemned the senseless violence on Wednesday, but I was particularly struck by one comment by former President George W. Bush, who wrote, “This is how election results are disputed in a banana republic — not our democratic republic” (Wamsley 2021).

The common moniker of a “banana republic” is often used to derogatorily characterize politically destabilized, so-called “third world” nations with rampant, anti-democratic corruption and class inequality, imagining that such things are only present outside the United States. As a linguist, I am interested in the usage and circulation of terms, and in the importance of understanding the origins of these terms. I think such a comment requires context and understanding of how the term “banana republic” itself originated, particularly because the intended usage can be unintentionally insulting to our friends in other nations, as it often overlooks the direct connections to the intentional destabilization of Central American governments ironically caused by powerful political and corporate interests in the United States. Likewise, it perpetuates the dangerous Eurocentric fiction of white supremacy, and it assumes an inferiority of these nations as being beneath the “first world,” which is both unfair and inaccurate. Such uses of this term overlook the responsibility our government bears in both causing and supporting these very anti-democratic political circumstances in other nations, as well as the parallels with our current tragic circumstances.

The term “banana republic” originated from the writing of O. Henry, the pen name of William Sydney Porter, who coined the term in his 1904 novel Cabbages and Kings (taken from the Lewis Carroll poem The Walrus and the Carpenter), about a fictitious Central American country called the Republic of Anchuria. This was based upon his own experiences in Honduras and his observations of the powerful fruit companies from the United States which had a profound impact on destabilizing Central American nations like Honduras and Guatemala for the purposes of their own profit through exporting the bountiful produce of these nations through exploiting cheap labor (Eschner 2017).

As we know from the well-documented history of Guatemala as detailed in Bitter Fruit: the Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala (Schlesinger & Kinser 1982, revised in 2005), the United States government was heavily involved with multiple dictators that favored the United Fruit Company (UFCO), culminating in the 1954 coup d’etat in Guatemala orchestrated and carried out by the CIA, which removed the democratically elected Jacobo Árbenz from power. Árbenz had instituted a popular policy of agrarian reform that sought to return unused land owned by the UFCO to poor farmers, many of which were Maya people who were forced to work as cheap labor in the fincas, the plantations owned by the UFCO.

Both the United States Secretary of State at the time, John Foster Dulles, and his brother, Allan Dulles, the Director of the CIA, had ties to the United Fruit Company, both having worked for the law firm which represented them. Because of these and other close ties, the UFCO successfully lobbied the U.S. Government under President Eisenhower to stage a coup through the CIA by playing into the fears of the Red Scare, inaccurately claiming that Árbenz was a communist. However, it was the United Fruit Company that was primarily concerned with its profits, which were greater than the GDP of Guatemala itself, and unjustly built on the backs of exploited people dispossessed from their traditional lands. The result was that Árbenz was forcibly deposed in 1954, leading to four decades of military dictatorships that were supported and armed by the United States government—ultimately leading to rampant human rights abuses and the genocide of tens of thousands of Maya people during the tragic and painful period that has become known as la Violencia.

In 1999, following the signing of the 1996 Peace Accords that ended the formal conflict in Guatemala, President Clinton finally issued an official apology to the Guatemalan government for the unjust involvement and support of dictatorships in Guatemala by the United States (Broder 1999). Here, in part, is Clinton’s apology:

“For the United States, it is important that I state clearly that support for military forces and intelligence units which engaged in violence and widespread repression was wrong, and the United States must not repeat that mistake…We must and will, instead, continue to support the peace and reconciliation process in Guatemala.”

While the United States prides itself on serving as an unshakeable example of democracy for the rest of the world, this sits uncomfortably for those who have been directly impacted by the decidedly anti-democratic actions our government has taken against other democratically elected governments when it has served corrupt interests of those in power. I do not intend for this to minimize the current crisis by casting aspersions on the problematic history of the United States and its history of anti-democratic practices. Rather, it is in my hope that we can all be better than this and that we can continue to learn from our mistakes.

It serves the greater good for us to understand the truth of our own history and how that history intersects with the history of our neighbors and friends among the Maya people we work with, who continue to bravely rebuild their lives and reconnect to a history that has been forcibly and repeatedly taken from them. I see the work we do as directly connected to taking some responsibility for reparations for what our nation has done, and I do hope we can return to that work as soon as possible this year.

I think it is worth remembering all of this in this current moment of crisis, and reflecting on the fragility of democracy itself, both at home and abroad, as well as reflecting on the devastating and dangerous consequences of attempting to overturn democratically elected governments based on falsehoods, selfishness, and greed. In this moment of national reckoning, I think it is important to acknowledge how easy it can be for selfish actors to abuse their power to manipulate and thwart the goals of democratic societies, particularly through the promotion of nationalist fictions of white supremacy, and it is of paramount importance in these moments to tell the truth about ourselves and about our shared past so that we do not repeat these mistakes. We are learning that we are all equal after all, and that we may yet live up to the promise of equality upon which our imperfect nation was built. We are equally vulnerable to anti-democratic abuses of power, just as we are not immune to a virus that has now taken over 375,000 lives in the United States, and nearly two million lives globally.

In the future, if we choose to use the term “banana republic” to describe another nation, or our own, I would hope that we use it with a more honest understanding where that term comes from, and I hereby invite all of us to learn its true meaning as connected to the history of the United States and its damaging, antidemocratic entanglements in other nations.

May we all have a safe, healthy New Year in pursuit of truth, happiness, and mutual understanding beyond our borders. May there especially be peace and healing in all of our nations in the coming weeks, months, and years to come. The time has come, and we’ve got work to do.

Yum Bo’otik, Sib’alaj Maltyox,

Michael Grofe, President

MAM

“La United Fruit Co.”

When the trumpet sounded

everything was prepared on earth,

and Jehovah gave the world

to Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, and other corporations.

The United Fruit Company

reserved for itself the most juicy

piece, the central coast of my world,

the delicate waist of America.

It rebaptized these countries

Banana Republics,

and over the sleeping dead,

over the unquiet heroes

who won greatness,

liberty, and banners,

it established comic opera:

it abolished free will,

gave out imperial crowns,

encouraged envy, attracted

the dictatorship of flies:

Trujillo flies, Tachos flies

Carias flies, Martinez flies,

Ubico flies, flies sticky with

submissive blood and marmalade,

drunken flies that buzz over

the tombs of the people,

circus flies, wise flies

expert at tyranny.

With the bloodthirsty flies

came the Fruit Company,

amassed coffee and fruit

in ships which put to sea like

overloaded trays with the treasures

from our sunken lands.

Meanwhile the Indians fall

into the sugared depths of the

harbors and are buried in the

morning mists;

a corpse rolls, a thing without

name, a discarded number,

a bunch of rotten fruit

thrown on the garbage heap.

~Pablo Neruda, Canto General (1950)

Versión Español

6 Ajaw 3 Muwan (8 de enero de 2021): De Coles y Reyes: Las “Repúblicas Bananeras” y la fragilidad pasada y presente de la democracia

Con gran pesar, escribo esto en un momento de grave crisis nacional en los Estados Unidos, aún sin resolver, en medio de la prolongada catástrofe de una pandemia mundial que todos seguimos sufriendo. Ha llegado un nuevo año en el calendario gregoriano, con la promesa de una vacuna que algunos de mis amigos ya han recibido, pero que todavía no están disponibles para todos. En lo que serán dos semanas de incertidumbre, una nueva administración presidencial llega al poder en Estados Unidos. Aunque carecemos de informes de campo actuales para publicar, esperaba poder simplemente desearnos a todos un año más feliz y esperanzador, lo que ciertamente deseo para todos, ahora más que nunca. Pero siento que ahora no es el momento de guardar silencio sobre lo que está sucediendo. Por favor, perdonen mi alejamiento de nuestros temas habituales al pasar a los eventos actuales, pero hay un hilo que creo que debe explorarse y que nos conecta con una historia compartida menos conocida entre los Estados Unidos y los mayas que a menudo no se discute o se reconoce.

El intento de golpe de estado y la invasión forzada y trágicamente mortal del edificio del Capitolio de los Estados Unidos el 6 de enero ha sido una experiencia nueva e impactante para los ciudadanos de los Estados Unidos, que se enorgullecen de ser el faro global de la democracia. Esta insurrección sigue siendo un recordatorio doloroso, pero importante, de la fragilidad de la democracia en sí, y es importante que reconozcamos que este tipo de eventos y sus trágicas secuelas no son desconocidos para gran parte del resto del mundo, en particular para nuestros amigos mayas en Centroamérica, quienes están viendo esto desde afuera y sin duda lo comparan con sus propias historias dolorosas de golpes de estado, que han sido mucho más mortíferos y organizados que este.

Con gran preocupación y sin dudarlo, los líderes mundiales y los ex presidentes de Estados Unidos por igual han condenado justificadamente la violencia sin sentido del miércoles, pero me llamó particularmente la atención un comentario del ex presidente George W. Bush, quien escribió: “Así es como se disputan los resultados de las elecciones en una república bananera, no en nuestra república democrática” (Wamsley 2021).

El apodo común de “república bananera” se usa a menudo para caracterizar despectivamente a las naciones políticamente desestabilizadas del llamado “tercer mundo”, con una corrupción desenfrenada y antidemocrática y gran desigualdad de clases, imaginando que tales cosas solo están presentes fuera de Estados Unidos. Como lingüista, me interesa el uso y la circulación de términos y la importancia de comprender el origen de estos términos. Creo que tal comentario requiere contexto y comprensión de cómo se originó el término “república bananera”, en particular porque el uso previsto puede ser un insulto involuntario para nuestros amigos en otras naciones, ya que a menudo pasa por alto las conexiones directas con la desestabilización intencional de los gobiernos centroaméricanos, causados irónicamente por poderosos intereses políticos y corporativos en los Estados Unidos. Asimismo, perpetúa la peligrosa ficción eurocéntrica de la supremacía blanca y presupone una inferioridad de estas naciones como inferiores al “primer mundo”, lo cual es injusto e inexacto. Tales usos de este término pasan por alto la responsabilidad que tiene nuestro gobierno de causar y apoyar estas circunstancias políticas antidemocráticas en otras naciones, así como los paralelismos con nuestras trágicas circunstancias actuales.

El término “república bananera” se originó a partir de la escritura de O. Henry, el seudónimo de William Sydney Porter, quien acuñó el término en su novela de 1904 Cabbages and Kings (“Coles y Reyes”, tomado del poema de Lewis Carroll La Morsa y el Carpintero), sobre un país centroamericano ficticio llamado República de Anchuria. Esto se basó en sus propias experiencias en Honduras y sus observaciones de las poderosas empresas frutícolas de los Estados Unidos, que tuvieron un profundo impacto en la desestabilización de naciones centroamericanas como Honduras y Guatemala, buscando su propio beneficio mediante la exportación de la abundante producción de estas naciones, por medio de la explotación de mano de obra barata (Eschner 2017).

Como sabemos por la bien documentada historia de Guatemala, como se detalla en Bitter Fruit: la historia no contada del golpe estadounidense en Guatemala (Schlesinger & Kinser 1982, revisada en 2005), el gobierno de los Estados Unidos estuvo muy involucrado con múltiples dictadores que favorecían a la United Fruit Company (UFCO) y que culminó con el golpe de estado de 1954 en Guatemala, orquestado y llevado a cabo por la CIA, que sacó del poder al presidente electo democráticamente Jacobo Árbenz. Árbenz había instituido una política popular de reforma agraria que buscaba devolver las tierras en desuso propiedad de la UFCO a los agricultores pobres, muchos de los cuales pertenecían a grupos mayas, obligados a trabajar como mano de obra barata en las fincas y plantaciones propiedad de la UFCO.

Tanto el entonces secretario de Estado de los Estados Unidos, John Foster Dulles, como su hermano, Allan Dulles, director de la CIA, tenían vínculos con la United Fruit Company, y ambos habían trabajado para el bufete de abogados que los representaba. Debido a estos y otros lazos cercanos, la UFCO presionó con éxito al gobierno de los Estados Unidos bajo el presidente Eisenhower para que organizara un golpe de estado a través de la CIA, jugando con los temores de la llamada “Red Scare”, afirmando erróneamente que Árbenz era comunista. Sin embargo, la United Fruit Company se preocupaba principalmente por sus ganancias, que eran mayores que el PIB de la propia Guatemala, mismas que se habían construido injustamente sobre las espaldas de personas explotadas y desposeídas de sus tierras tradicionales. El resultado fue que Árbenz fue depuesto por la fuerza en 1954, lo que llevó a cuatro décadas de dictaduras militares que fueron apoyadas y armadas por el gobierno de los Estados Unidos, y que en última instancia condujo a abusos desenfrenados de los derechos humanos y al genocidio de decenas de miles de mayas durante el trágico y doloroso período que se ha dado a conocer como la Violencia.

En 1999, luego de la firma de los Acuerdos de Paz de 1996 que pusieron fin al conflicto formal en Guatemala, el presidente Clinton finalmente emitió una disculpa oficial al gobierno guatemalteco por la participación injusta y el apoyo a las dictaduras en Guatemala por parte de Estados Unidos (Broder 1999). Aquí, en parte, está la disculpa de Clinton:

“Para Estados Unidos, es importante que yo afirme claramente que el apoyo a las fuerzas militares y las unidades de inteligencia que participaron en la violencia y la represión generalizada fue equivocada y que Estados Unidos no debe repetir ese error… Debemos y seguiremos, en cambio, apoyando el proceso de paz y reconciliación en Guatemala.”

Si bien Estados Unidos se enorgullece de servir como un ejemplo inquebrantable de democracia para el resto del mundo, esto resulta incómodo para aquellos que han sido directamente afectados por las acciones decididamente antidemocráticas que nuestro gobierno ha tomado contra otros gobiernos elegidos democráticamente, cuando esto ha servido a los intereses corruptos de los que están en el poder. No pretendo que esto minimice la crisis actual arrojando calumnias sobre la problemática historia de Estados Unidos y su historia de prácticas antidemocráticas. Más bien, tengo la esperanza de que todos podamos ser mejores que esto y podamos seguir aprendiendo de nuestros errores.

Nos sirve para un bien mayor entender la verdad de nuestra propia historia y cómo esa historia se cruza con la historia de nuestros vecinos y amigos entre los mayas con los que trabajamos, quienes continúan reconstruyendo valientemente sus vidas y reconectándose con una historia que ha les ha sido arrebatada repetidamente por la fuerza. Veo el trabajo que hacemos como algo directamente relacionado con asumir alguna responsabilidad por las reparaciones de lo que ha hecho nuestra nación, esperando que podamos volver a ese trabajo lo antes posible este año.

Creo que vale la pena recordar todo esto en este momento de crisis actual, y reflexionar sobre la fragilidad de la democracia en sí, tanto en el país como en el exterior, así como reflexionar sobre las devastadoras y peligrosas consecuencias de intentar derrocar gobiernos elegidos democráticamente sobre la base de falsedades, egoísmo y codicia. En este momento de ajuste nacional de cuentas, creo que es importante reconocer lo fácil que puede ser para los actores egoístas abusar de su poder para manipular y frustrar los objetivos de las sociedades democráticas, particularmente a través de la promoción de las ficciones nacionalistas de la supremacía blanca. Es de suma importancia en estos momentos decir la verdad sobre nosotros mismos y sobre nuestro pasado compartido para no repetir estos errores. Estamos aprendiendo que todos somos iguales después de todo, y que aún podemos estar a la altura de la promesa de igualdad sobre la cual se construyó nuestra imperfecta nación. Somos igualmente vulnerables a los abusos de poder antidemocráticos, del mismo modo que tampoco somos inmunes a un virus que ahora ha cobrado más de 375.000 vidas en los Estados Unidos y casi dos millones de vidas en todo el mundo.

En el futuro, si elegimos usar el término “república bananera” para describir a otra nación o a la nuestra, espero que lo usemos con una comprensión más honesta sobre el origen de ese término, y por la presente los invito a todos a aprender su verdadero significado en relación con la historia de los Estados Unidos y sus enredos dañinos y antidemocráticos en otras naciones.

Deseo que todos tengamos un Año Nuevo seguro y saludable en la búsqueda de la verdad, la felicidad y el entendimiento mutuo más allá de nuestras fronteras. Que haya especialmente paz y reconciliación en todas nuestras naciones en las semanas, meses y años por venir. Ha llegado el momento y tenemos trabajo por hacer.

Yum Bo’otik, Sib’alaj Maltyox,

Michael Grofe, Presidente

MAM

“La United Fruit Co.”

Cuando sonó la trompeta,

estuvo todo preparado en la tierra,

y Jehova repartió el mundo

a Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, y otras entidades:

la Compañía Frutera Inc.

se reservó lo más jugoso,

la costa central de mi tierra,

la dulce cintura de América.

Bautizó de nuevo sus tierras

como “Repúblicas Bananas,”

y sobre los muertos dormidos,

sobre los héroes inquietos

que conquistaron la grandeza,

la libertad y las banderas,

estableció la ópera bufa:

enajenó los albedríos

regaló coronas de César,

desenvainó la envidia, atrajo

la dictadura de las moscas,

moscas Trujillos, moscas Tachos,

moscas Carías, moscas Martínez,

moscas Ubico, moscas húmedas

de sangre humilde y mermelada,

moscas borrachas que zumban

sobre las tumbas populares,

moscas de circo, sabias

moscas entendidas en tiranía.

Entre las moscas sanguinarias

la Frutera desembarca,

arrasando el café y las frutas,

en sus barcos que deslizaron

como bandejas el tesoro

de nuestras tierras sumergidas.

Mientras tanto, por los abismos

azucarados de los puertos,

caían indios sepultados

en el vapor de la mañana:

un cuerpo rueda, una cosa

sin nombre, un número caído,

un racimo de fruta muerta

derramada en el pudridero.

~ Pablo Neruda, Canto General (1950)