Dear readers,

Over recent years we have seen glyph workshops of many kinds at many levels, but it seems to me that none can be more significant for future epigraphy in indigenous Maya areas than the introduction of epigraphy to the school teachers themselves, who then in turn can multiply the knowledge exponentially in public schools. I present today two such programs, one from Yucatan and one from Guatemala. I have asked the leaders of these two movements to tell us in their own words why this is important.

Bruce Love, President, MAM

TEACHING MAYA GLYPHS THROUGH THE PROGRAM KO’ONE’EX KANIK MAAYA

by Prof. Milner Rolando Pacab Alcocer

January, 2016

One of the great challenges in education that is imparted to the Maya children of Yucatan, from any geographical part of our state, is to provide quality education that has relevance, seeking to deliver the skills that are expected for childhood development, and skills that have meaning, that are linked to daily life.

Under this premise, the Bureau of Indigenous Education notes that in urban communities of our state many children, despite having Maya descent, have Spanish as their mother tongue and do not have opportunities to develop and strengthen their identity and sense of belonging to the culture of their grandparents.

On behalf of these children, Ko’one’ex Kanik Maaya program was established as an alternative to contribute to the development of learning, assessment, and appreciation of the knowledge of their ancestors. This not only involves learning the Mayan language, but also the extensive cultural knowledge and experience that is carried through language, such as its traditions, customs, and mathematical and astronomical knowledge that are still present and are useful in the daily lives of the Maya people.

From this perspective, the education that is offered to these children is intended to cover the entirety of the worldview of our mother culture, and this is the line of work that the institution has set for the implementation of this educational program in 85 urban schools where it operates.

However, despite more than 20 years since its implementation, it has not considered the teaching of the ancient script of our grandparents as part of its contents until this school year, with the concept that the Ko’one’ex Kanik Maaya program could be the means for teaching and dissemination of epigraphy to new generations.

Besides being an innovation in the contents of the 25 schools participating in this school year, there is a great opportunity for the Mayan glyphs to break loose from the idea that they are the exclusive field for researchers and experts, for it can be a component that strengthens the identity of our children who learn to handle the syllabary to read and produce their own texts through this epigraphic system and it can awaken interest in this field of study for future researchers and disseminators of this valuable writing system in which much remains to be discovered.

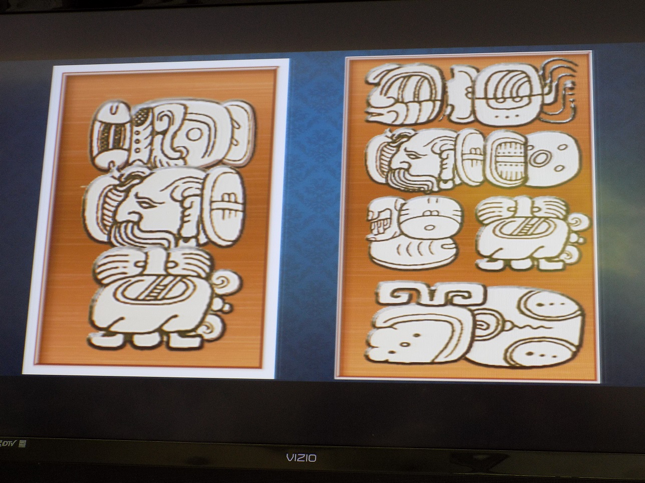

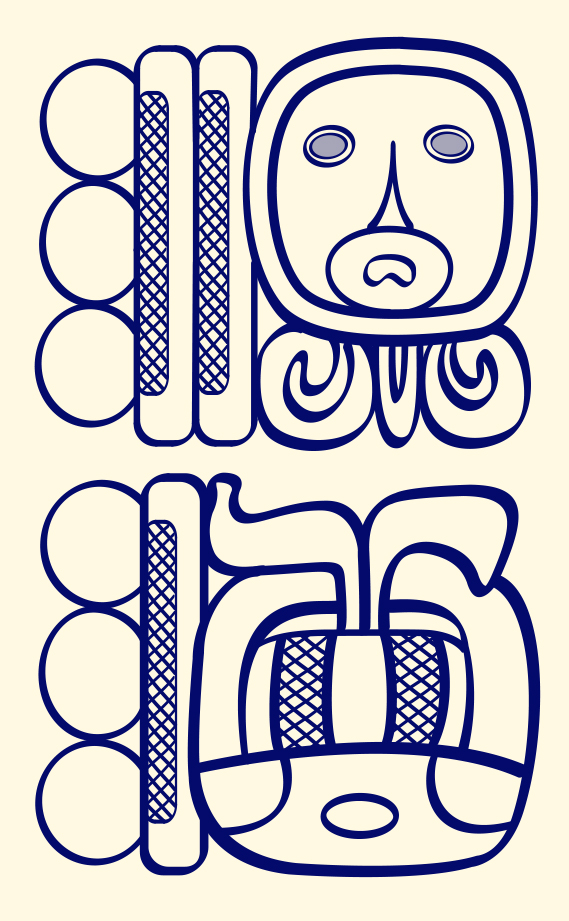

Poster from the Ko’ox Kanik Maaya school program.

Left side: ko-o-ne-e-xa ka-ni-ki ma-ya; Ko’one’ex kanik Maya; “Let’s learn Maya.”

Right side: ta-na i-ni ka-ni-ki tz’i-bi ye-te-le ma-ya wo-jo-bo; Tan in kanik tz’ib yetel Maya wojo’ob; “I am learning ancient writing with Maya glyphs.”

Queridos lectores:

En los últimos años, hemos sido testigos de la organización de muchos tipos de talleres para la enseñanza de los glifos mayas a diferentes niveles. Sin embargo, soy de la opinión de que nada resultará tan importante para la epigrafía futura de las áreas indígenas mayas como la introducción del estudio de la epigrafía entre los mismos maestros de escuela, quienes podrán así multiplicar exponencialmente su conocimiento en las escuelas públicas. Me complace presentar el día de hoy dos programas de estas características: uno en Yucatán y otro en Guatemala. He pedido a los organizadores de estas dos iniciativas que nos expliquen con sus propias palabras la importancia de las mismas.

Bruce Love, Presidente, MAM

LA ENSEÑANZA DE LOS GLIFOS MAYAS MEDIANTE EL PROGRAMA KO’ONE’EX KANIK MAAYA

por Profr. Milner Rolando Pacab Alcocer

Enero de 2016

Uno de los grandes retos de la educación que se imparte a los niños mayas en el estado Yucatán es brindarles una educación de calidad y con pertinencia, buscando otorgarles la oportunidad de adquirir las competencias que se espera desarrollen todos los niños y niñas de cualquier parte de la geografía de nuestro país y que ésta sea significativa, es decir, vinculada a su vida diaria para que le encuentren sentido.

Bajo esta premisa, la Dirección de Educación Indígena, no pierde de vista que en las comunidades urbanas de nuestro estado, viven niños que pese a tener ascendencia maya, tienen al español como lengua materna y no tienen oportunidades para desarrollar y fortalecer su identidad y sentido de pertenencia a la cultura de la que proceden sus abuelos.

En atención a estos niños se instauró el programa Ko’one’ex Kanik Maaya como una alternativa para contribuir al desarrollo del aprendizaje, la valoración y el aprecio de los conocimientos de sus ancestros. Esto implica el aprendizaje de la lengua maya, pero también del gran bagaje cultural que se manifiesta y tiene su continuidad por medio del lenguaje, tales como sus tradiciones, sus costumbres y los conocimientos matemáticos y astronómicos que aún hoy están presentes y son de utilidad en la vida cotidiana del pueblo maya.

Desde esta perspectiva, la enseñanza que se les brinda a estos niños se pretende abarque la integralidad de la cosmovisión de nuestra cultura madre, siendo esta la línea de trabajo que se ha trazado la institución para la aplicación de este programa educativo en las 85 escuelas urbanas en donde tiene presencia.

Sin embargo, pese a los más de 20 años que se tiene implementándolo, no se había considerado la enseñanza de la escritura antigua de nuestros abuelos como parte de sus contenidos, hasta el presente ciclo escolar en donde visualizo la gran posibilidad de que el sistema educativo sea artífice para la enseñanza y la difusión de los glifos a las nuevas generaciones por medio de este Programa.

Sin duda, además de constituir una innovación en los contenidos de las 25 escuelas que participan en el presente ciclo escolar, constituye la gran oportunidad para hacer que los glifos mayas pierdan el carácter de área de estudio exclusivo de investigadores y expertos en el tema, para ser recuperado como un elemento que refuerce la identidad de nuestros niños, quienes además de que aprenden a manejar el silabario para leer y producir textos propios por medio de su sistema epigráfica, se pretende también despertarles el interés para profundizar en este campo de estudio y sean los futuros investigadores y difusores de este valioso sistema de escritura en el que aún queda mucho por descubrir.

Cartel del programa escolar Ko’ox Kanik Maaya. El lado izquierdo: ko-o-ne-e-xa ka-ni-ki ma-ya; Ko’one’ex kanik Maya; “Vamos a aprender Maya.” El lado derecho: ta-na i-ni ka-ni-ki tz’i-bi ye-te-le ma-ya wo-jo-bo; Tan in kanik tz’ib yetel Maya wojo’ob; “Estoy aprendiendo escritura antigua con glifos mayas.”

IMPORTANCE OF MAYA EPIGRAPHY IN INTERCULTURAL BILINGUAL EDUCATION IN GUATEMALA

by Victor Maquin, Maya Q’eqchi’ Educator

January, 2016

(please see our blog 8 Ajaw 8 Xul, July 19, 2015, for the first El Estor workshop)

In El Estor, Izabal, in the north of Guatemala, during 2015 two training workshops on Maya epigraphy were conducted aimed at Maya Q’eqchi’ teachers practicing in public schools to strengthen processes to recover the ancient Mayan knowledge with the idea of reproducing it as classroom content.

From my point of view, I perceived that this type of training was necessary and essential for boosting the capacities of teachers, due to the limited opportunities for training with cultural relevance that exists within the national education system, which has not yet taken seriously Intercultural Bilingual Education, which is one of the main demands of the indigenous population, which is currently the majority despite official statistical indexes that try to make invisible this growing reality in urban and rural areas.

In this context, educational communities are scenes in which we encounter cultural expressions of many varied regions; in particular in the case of El Estor, Izabal, however, besides the Q’eqchi’ there is the presence of Achi, Poqomchi’, K’iche’, and Garifuna, who continue to use their languages, traditions, and customs, forming a multicultural space that enriches all groups.

Thus, the workshops on Maya epigraphy, aimed at Maya Q’eqchi’ teachers, have had a positive impact on the educational communities, mainly reaffirming the ancestral identity and pride in descent from the ancient Mayan culture for the teachers themselves, who then transmit the teachings to students to regain the ability to read the writing on the monuments and Maya codices.

In this sense, I think Intercultural Bilingual Education in Guatemala still has a long way to go, however in many places in the national geography teachers come with a high potential that are contributing to the construction of the ancestral identity as part of the process of claiming of the rights of the Maya people.

Consequently, it is necessary that the Ministry of Education recognizes that Guatemala is a multicultural and multilingual country, where through a culturally relevant education, the Maya people can intervene in the social, political and cultural scene as part of the struggle to achieve the ability of our people to build for ourselves our own historical destiny.

The goal of Maya education is that schools are centers of culture and cultural identity to promote values, principles, and knowledge from our own reality, from our Maya worldview, i.e., our own way of seeing and interpreting the world of our ancestors.

Laa’o jo ‘aj ralch’och’ li qak’ulub wank “chi li roksinkil nawom xe’xkanab ‘chaq eb’ li qana ‘qayuwa’. We as Maya peoples have the right to regain the use of the knowledge that we inherited from our ancestors.

Q’eqchi’ Maya school teachers from Izabal Department, Guatemala. Bottom row on far right: Vicor Maquin, local organizer and participant in Ocosingo Congress of Maya Epigraphers; upper row on far right: Q’eqchi’ epigrapher Hector Xol.

IMPORTANCIA DE LA EPIGRAFÍA MAYA EN LA EDUCACIÓN BILINGÜE INTERCULTURAL EN GUATEMALA

por Victor Maquin, Educador Maya Q’eqchi’

Enero de 2016

(por favor vea nuestro blog 8 Ajaw 8 Xul, 19 de julio 2015, para el primer taller de El Estor)

En El Estor, Izabal, en la zona norte de Guatemala, durante el año 2015 se realizaron dos talleres de capacitación sobre epigrafía Maya dirigido a docentes Maya Q’eqchi’ en ejercicio en centros educativos públicos, para fortalecer los procesos encaminados a recuperar el conocimiento ancestral maya, con la idea de replicar los contenidos en las aulas escolares.

Desde mi particular punto de vista, he percibido que este tipo de actividades de capacitación son necesarias e indispensables para potenciar las capacidades de los docentes, debido a las escasas oportunidades de formación con pertinencia cultural que existen dentro del Sistema Educativo Nacional, que todavía no ha tomado en serio la Educación Bilingüe Intercultural, que es una de las principales exigencias de la población indígena del país, que actualmente es la mayoritaria a pesar de los índices estadísticos oficiales que tratan de invisibilizar esta creciente realidad en las áreas urbanas y rurales.

En este contexto, las comunidades educativas son escenarios del encuentro de expresiones culturales de todas las regiones, de la cultura Q’eqchi’ en particular, en el caso de El Estor, Izabal, no obstante, existe presencia de población Achi, Poqomchi’, K’iche’ y Garífuna, que siguen utilizando sus idiomas, sus tradiciones y costumbres, configurando un espacio multicultural que enriquece a todos los conglomerados.

De esta forma, los talleres de capacitación sobre Epigrafía Maya, dirigido a docentes Maya Q’eqchi’, han tenido un impacto positivo en las comunidades educativas, principalmente para reafirmar la identidad ancestral y el orgullo por descender de la milenaria Cultura Maya, de parte de los mismos docentes, que luego transmiten las enseñanzas a los estudiantes para recuperar la capacidad de leer lo escrito en los monumentos y códices mayas.

En este sentido, creo que la Educación Bilingüe Intercultural en Guatemala tiene todavía un largo camino que recorrer, no obstante en muchos lugares de la geografía nacional surgen docentes con un alto potencial que están contribuyendo en la construcción de la identidad ancestral, como parte del proceso de reivindicación de los derechos de los pueblos mayas.

En consecuencia, es preciso que el Ministerio de Educación reconozca que Guatemala es un país pluricultural y multilingüe, donde a través de una educación con pertinencia cultural, la población maya podamos intervenir en el escenario social, político y cultural, como parte de la lucha por lograr la capacidad de nuestros pueblos para construir por nosotros mismos nuestro propio destino histórico.

La meta es lograr la Educación Maya para que los centros educativos sean centros de cultura y de identidad cultural para promover valores, principios, conocimientos, desde nuestra propia realidad, desde nuestra Cosmovisión Maya, es decir, nuestra propia forma de ver e interpretar el mundo de nuestros ancestros.

Laa’o jo’ aj ralch’och’ wank li qak’ulub’ chi roksinkil li nawom xe’xkanab’ chaq eb’ li qana’ qayuwa’. Nosotros como pueblos mayas tenemos el derecho de recuperar el uso de los conocimientos que nos heredaron nuestros ancestros.

Que bueno que haya enseñanza de glifos y yo estoy interesada en aprender me podrías dar clases gracias