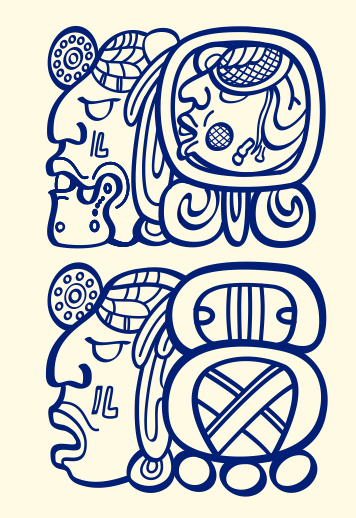

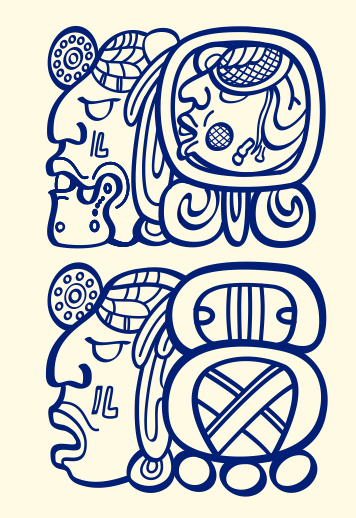

13 Ajaw 3 Sip: Drawing by Jorge Pérez de Lara

Receiving diplomas of participation in San Juan Chamelco

Beneath the Majestic Ceiba: Q’eqchi’ teachers explore the ancient script in San Juan Chamelco, Guatemala

This month, as we are all mostly confined to our homes, we bring you good tidings from Leonel Pacay Rax and Byron Rafael Xi Tot in San Juan Chamelco, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Leonel and Byron facilitated a three-part workshop on Maya writing from April to December, 2019 with 21 local Q’eqchi’ teachers.

Among the approximately 30 languages in the Mayan language family, Q’eqchi’ is the second most widely spoken Mayan language (after K’iche’) with well over a million speakers, and it has the distinction of having the highest rate of monolingual speakers who do not speak other languages. In addition, although Q’eqchi’ belongs to the K’ichean subfamily of Mayan languages, which are mostly found in the Highlands of Guatemala, it contains a large number of loanwords from the Ch’olan and Yucatecan languages that are typically associated with the Classic period Maya script. Though Q’eqchi’ speakers are found in the relatively remote area of the Alta Verapaz, there has been a longstanding contact between Q’eqchi’ speakers and speakers of the Lowland Mayan languages (see Soren Wichmann and Kerry Hull 2009

“Loanwords in Q’eqchi’, a Mayan Language of Guatemala’ in Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Martin Haspelmath, Uri Tadmor, eds. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.)

https://web.archive.org/web/20110915143115/http://wold.livingsources.org/language/34

This brings up an interesting and complex issue in our collective work to revitalize the Maya script for all Maya people. Namely, linguists have carefully classified the 30 different Mayan languages as all related to single ancestral tongue that most likely existed over 3,000 years ago, referred to as proto-Mayan, since we do not know the original name. Interestingly, the name “Mayan” itself derives from the name Maaya’-T’àan, or the Yucatec language, which was the first Mayan language that was documented by the Spanish, and then the term was used by archaeologists to refer to the Ancient Maya, as well as by linguists to refer to all speakers of Mayan languages.

As the decipherment of the Maya script progressed in the late 20th Century, clear evidence emerged that the lingua franca of the Classic Script was most closely related to an extinct but documented language called Ch’olti’an, which was part of the Eastern Ch’olan branch of the Mayan language family. The highly endangered language of Ch’orti, spoken in Honduras and in Chiquimula, Guatemala, is apparently the next closest relative, though neither one of these languages is identical with the script from the Classic period, just as Spanish is different from its ancestral Latin. Much as Latin was used in the Roman Empire, the language of the Classic script was an elite, prestige language that was apparently quite standardized. However, there is clear evidence that the Maya script was used to write Yucatecan languages, as well as Tzeltalan, and possibly K’ichean. We likewise see examples of even non-Mayan Nahua words in the glyphs (see Kettunen and Helmke, 2020: 13). Wayeb Resources-Kettunen and Helmke

The extent to which speakers of other Mayan languages used hieroglyphic writing is not fully known, though scribal languages are typically used by diverse language speakers. Tragically, all but four of the codices have been destroyed, yet even the K’iche’ Popol Vuh itself was apparently transcribed from an original written version in some form. With advances in the decipherment of the Maya script, speakers of many different Mayan languages have taken a great interest in learning this ancient writing system which was used to write a language related to their own languages, and they invited epigraphers to teach them what they knew, which is how MAM first developed as an organization. As our Maya colleagues have learned to read and write in this ancient script, they have recognized their common Mayan heritage, including the very familiar calendars still kept by living Maya people, and they have taken great pride in valuing their own languages and cultures in the face of enormous pressures to assimilate. Insights gained from living Maya traditions in both the Highlands and Lowlands have helped archaeologists and epigraphers to interpret the Ancient Maya past. Imagine how many more insights may be gained by having Maya people participate more fully in this effort as Aj Tz’iibob, epigraphers, and archaeologists themselves.

Living writing systems naturally change and adapt, and our Maya colleagues have each adapted the Maya script to write and record their own living Mayan languages, sometimes necessitating the need for a few new syllabic glyphs to represent sounds in the Highland Mayan languages that do not exist in the lowland script, such as /q/, /q’/, /r/ and /r/. Even modern Ch’orti uses the /r/ sound that did not exist in its close cousin in the Classic script.

In a very real way, this script is again a living connection that brings together all Maya people with a common heritage that have suffered under colonial rule, much as the European Renaissance emerged following the Dark Ages, after which Europeans of all different languages and nations looked to the Greek and Roman cultures as their common cultural heritage, inspiring great works of art, literature, science, and culture.

Now, all European languages are written using descendants of the Greek script, which gave rise to both the Roman and Cyrillic scripts we see today. No longer are these scripts confined to just writing Greek and Latin. They allow us to learn about our ancient history and our ancestors who preceded us, but they also allow us to write our own histories, and to be a part of making history ourselves.

What we are seeing now with the interest in the Classic Maya script among Maya people of all different languages is very much a Maya Cultural Renaissance, and it is a great honor and privilege for us to be a part of this at MAM as we witness history in the making, and as we celebrate the achievements of Maya cultures, past and present.

Our hearts go out to all of our greater human family who are suffering in this current pandemic, and especially to our many Maya colleagues at this difficult time. We stand with you and send this message of hope, health, and more life as our planet begins to heal. This is not the first pandemic humanity has endured, and Maya people suffered greatly when the diseases of Europe ravaged native populations many centuries ago. We look forward to emerging from this pandemic with strength, more dedicated to our cause, and with great resolve for making the Fifth International Congreso on Ancient Maya Writing next year a powerful, historical event.

To all of our generous supporters, thank you all for being a part of making history.

B’antiox,

Michael Grofe, President

MAM

Epigraphy Workshop Report

Accomplished thanks to the support provided by Mayas for Ancient Mayan–MAM

Where the activity took place

San Juan Chamelco Parish Hall

Dates: April 16, December 23 and 27, 2019

Participants: 11 Women 10 Men

Language Group Q’eqchi’

Facilitators: Leonel Pacay Rax and Byron Rafael Xi Tot

GENERAL INFORMATION

Geographic Location

San Juan Chamelco, founded in 1558, is located in the department of Alta Verapaz, only 7 km from the departmental headwaters. Upon arrival, you can see its majestic ceiba, which is located in the park of the central Catholic church, which is very old. On the side of the church is the former headquarters of the municipality and the market.

13 Ajaw 3 Sip: Dibujo de Jorge Pérez de Lara

Entrega de diplomas de participación en San Juan Chamelco.

Bajo la Majestuosa Ceiba: Maestras y Maestros q’eqchís exploran la escritura antigua en San Juan Chamelco, Guatemala

Este mes, como todos estamos confinados principalmente en nuestros hogares, les traemos buenas noticias de San Juan Chamelco, en Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Leonel Pacay Rax y Byron Rafael Xi Tot facilitaron un taller de escritura maya de tres partes entre abril y diciembre de 2019, con 21 maestras y maestros q’eqchís.

Entre los aproximadamente 30 idiomas de la familia de lenguas mayas, el q’eqchí es la segunda lengua maya más hablada (después del k’iché), con más de un millón de hablantes. El q’eqchí tiene la distinción de tener la más alta tasa de hablantes monolingües (es decir, que no hablan ningún otro idioma). Además, aunque el q’eqchí pertenece a la subfamilia k’icheana de las lenguas mayas, que se encuentran principalmente en las tierras altas de Guatemala, incluye una gran cantidad de préstamos de las lenguas ch’olana y yucateca, que generalmente están asociadas con la escritura maya del período Clásico. Aunque los hablantes de q’eqchí se encuentran en un área relativamente remota de Alta Verapaz, hay una larga historia de contacto entre los hablantes de q’eqchí y los hablantes de las lenguas mayas de las tierras bajas. (ver Soren Wichmann y Kerry Hull 2009 “Loanwords in Q’eqchi’, a Mayan Language of Guatemala’ in Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Martin Haspelmath, Uri Tadmor, eds. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.) https://web.archive.org/web/20110915143115/http://wold.livingsources.org/language/34

Conforme el desciframiento de la escritura maya fue avanzando a fines del siglo XX, surgieron evidencias claras de que la lingua franca de la escritura clásica estaba más estrechamente relacionada con una lengua extinta pero documentada, llamada ch’oltí, que formaba parte de la rama oriental ch’olana de la familia de lenguas mayas. El ch’ortí, una lengua con alto riesgo de desaparecer, y que aún se habla en Honduras y en Chiquimula, en Guatemala, parece ser su pariente más cercano, aunque ninguno de estos idiomas es idéntico al de la escritura del período Clásico, del mismo modo en que el español es diferente de su latín ancestral. Al igual que el latín se usó en el imperio romano, la lengua de la escritura maya clásica era un lenguaje de élite y prestigio que aparentemente estaba bastante estandarizado. Sin embargo, existe evidencia clara de que la escritura maya se usó para escribir lenguas yucatecas, así como tzeltalanas y posiblemente k’icheanas. Incluso es posible hallar ejemplos de palabras nahuas no mayas (ver Kettunen y Helmke, 2011: 13). Wayeb Recursos-Kettunen y Helmke

Esto trae a colación un tema interesante y complejo en nuestro trabajo colectivo para revitalizar la escritura maya para todas las personas mayas. Es decir, una cuidadosa clasificación hecha por los lingüistas han llevado a la conclusión de que las 30 diferentes lenguas mayas están relacionadas con una sola lengua ancestral que probablemente existió hace más de 3.000 años y a la que nos referimos como proto-maya, ya que no conocemos su nombre original. Curiosamente, el nombre “maya” en sí se deriva del nombre maaya’-t’àan, o lengua yucateca, que fue el primer idioma maya que se documentó en español. Posteriormente, este nombre fue el que utilizaron tanto los arqueólogos para referirse a los antiguos mayas, como los lingüistas para referirse a todos los hablantes de lenguas mayas.

No se sabe con exactitud qué tanto pudieron haber hecho uso de la escritura jeroglífica los hablantes de otras lenguas mayas, si bien la lengua utilizada por los escribas suele utilizarse entre hablantes de diversas lenguas. Por desgracia y con la excepción de sólo cuatro, todos los códices fueron destruidos. No obstante, incluso el Popol Vuh de los k’ichés parece haber sido transcrito a partir de una versión original registrada por escrito de algún modo. Con los avances en el desciframiento de la escritura maya, los hablantes de muchos de los diferentes idiomas mayas han mostrado un gran interés en aprender este antiguo sistema de escritura, que se usaba para escribir un idioma relacionado con sus propios idiomas e invitaron a los epigrafistas a enseñarles lo que sabían. Es así como MAM nació como organización. En la medida en que nuestros colegas mayas aprendieron a leer y escribir en este antigua escritura, fueron reconociendo su herencia maya común, incluidos los calendarios muy familiares que aún se conservan entre los mayas vivos, naciendo así en ellos el orgullo de valorar sus propios idiomas y culturas frente a enormes presiones para asimilarse.

Los conocimientos adquiridos de las tradiciones mayas vivas, tanto en las tierras altas como en las tierras bajas, han ayudado a los arqueólogos y epigrafistas a interpretar el pasado maya antiguo. ¡Imaginemos cuánto más podrá avanzarse si los mayas participan más plenamente en este esfuerzo en calidad de Aj Tz’iibob, como epigrafistas e incluso como arqueólogos!

Los sistemas de escritura vivos cambian y se adaptan naturalmente, y cada uno de nuestros colegas mayas ha adaptado la escritura maya para escribir y registrar sus propios idiomas mayas vivos, teniendo a veces la necesidad de desarrollar algunos glifos silábicos nuevos para representar sonidos de los idiomas mayas de las tierras altas que no existen en la escritura maya del período clásico, como /q/, /q’/, /r/ y /r/. Incluso el ch’ortí moderno usa el sonido /r/ que no existía en su primo cercano en la escritura clásica.

De una manera muy real, esta escritura constituye nuevamente una conexión viva que reúne a todos los mayas con una herencia común que han sufrido bajo el dominio colonial, de la misma manera en que surgió el Renacimiento europeo después de la Edad Media, tras de lo cual los europeos de todas las lenguas y naciones diferentes consideraron a las culturas griega y romana como su patrimonio cultural común, inspirando grandes obras de arte, literatura, ciencia y cultura.

En la actualidad, todos los idiomas europeos se escriben usando sistemas que descienden de la escritura griega, que dio lugar a caracteres latinos y cirílicos que vemos hoy. Estos sistemas de escritura ya no se limitan a escribir sólo los idiomas griegos y latinos del pasado, sino que nos permiten aprender sobre nuestra historia antigua y sobre los antepasados que nos precedieron, pero también nos permiten escribir nuestras propias historias y ser parte de hacer historia nosotros mismos.

Lo que estamos viendo ahora con el interés existente en la escritura maya clásica entre los mayas de todos los idiomas es en gran medida un Renacimiento cultural maya, y es un gran honor y privilegio para nosotros ser parte de esto en MAM, al poder presenciar la historia en proceso y al celebrar los logros de las culturas mayas pasadas y presentes.

Nuestros corazones están con toda la gran familia humana que sufre en la actual pandemia , y especialmente con nuestros muchos colegas mayas en estos difíciles momentos. Estamos con ustedes y les enviamos este mensaje de esperanza, salud y más vida, a medida que nuestro planeta comienza a sanar. Esta no es la primera pandemia que ha sufrido la humanidad, y los mayas sufrieron mucho cuando las enfermedades de Europa asolaron a las poblaciones nativas hace muchos siglos. Esperamos salir de esta pandemia con más fuerza, más dedicados a nuestra causa y con una gran determinación para hacer del Quinto Congreso Internacional sobre Escritura Maya Antigua el próximo año un evento histórico y poderoso.

A todos nuestros generosos patrocinadores, y a todos nuestros colegas mayas, gracias por estar haciendo esta historia.

B’antiox,

Michael Grofe, Presidente

MAM

Informe Taller de Epigrafía

Realizado gracias al apoyo otorgado por Maya Antiguo para los Mayas—MAM

Lugar donde se realizó la actividad

Salón Parroquial San Juan Chamelco

Fechas: 16 de abril, 23 y 27 de diciembre 2019

Participantes: 11 Mujeres 10 Hombres Grupo Lingüístico Q’eqchi’

Facilitadores: Leonel Pacay Rax y Byron Rafael Xi Tot

INFORMACIÓN GENERAL

Ubicación geográfica

San Juan Chamelco, fundado en 1558, está situado en el departamento de Alta Verapaz, a solamente 7 km de la cabecera departamental. Al llegar, se nota su majestuosa ceiba, está situada en el parque de la iglesia católica central, la cual es muy antigua. A un costado de la iglesia se encuentra la antigua sede de la municipalidad y el mercado. Continue reading